I was sitting at a kitchen table in Sheffield with my friend (and the producer of my new album) Andy Bell. It was a washed out late summer day in-between the various lockdowns we had all been weathering in 2020. The rain was falling heavy on the garden and a squally breeze was ruffling the flower beds. I had come up to spend some time with him and generally talk about how we were going to get people into the album (which is called ‘Clifftown’ by the way and was born out of a desire I had for some years to articulate my experiences in my hometown, the seaside suburbia that is Southend-on-Sea).

“You should make a podcast about all the stories and characters” Andy said, or something to that effect. He’d visited me numerous times and knew how colourful an area it was. Inside I recoiled – the thought of interviewing people I knew about the things that went unsaid between us felt like prying, or worse making something grandiose out of the ordinary. But, I said I would try. I drove home days later plotting how I could pull this off…and then thought became research and I sent a few emails to people and some of these turned into interviews and then it happened, The Clifftown Podcast.

I wracked my brains for themes and ideas that wouldn’t be too obvious that would be interesting not just for me but others too. I kept circling back to the hidden histories and tall tales I had heard growing up here, romantic tales of smugglers and fleeing royalty and the grittier (but equally compelling) tales we heard from the old boys that used to prop up the bar in the Grand Hotel, stories of petty criminals trying to kill cows near Hadleigh Castle in order to sell the meat illegally but being so drunk they ended up shooting crossbow bolts into a tractor mistaking it for a sleeping Frisian. I’m obsessed with finding traces of past lives so this topic felt like a good place to start – I felt comfortable with what I was talking about and it seemed apt to start at a point where the place existed but I did not.

Brian Denny was an obvious choice for my first podcasting attempt. A naturally affable and warm man Brian is great for stories and local lore. Over the years we had regularly met to walk around the more desolate places of the county including the Dengie Peninsula (the site of one of the oldest largely intact churches in England, St Peter’s by the Wall in Bradwell-on-Sea, built in the 690s by the patron saint of Essex, St. Cedd) and the shores near Canewdon trying to picture the Battle of Ashingdon, which took place nearby and where King Cnut was victorious over the Saxon king, Edmund Ironside.

For the interview we met up in more anodyne surroundings on the edge of the suburban Highlands Estate in Leigh on Sea. We started talking straight away about the common myths of these parts – the highwayman Cutter Lynch and the Sea Witch Sarah Moore. In the podcast I gloss over the myth of Cutter Lynch simply because the wind ruined the quality of the recording. So, maybe it’s good summarise it here –

There’s a block of flats from the 1970s on the main London Road called Lapwater Court. In 1750 it was the site of a dilapidated and expansive residence called Leigh Park House. It was bought by a mysterious Mr Gilbert Craddock who subsequently visited the site and ordered renovations to take place. Towards the end of the renovations the local workmen were expecting, as was local custom, to receive ale from Mr Craddock for their work. Mr Craddock stated in no uncertain terms that if they wanted to drink rather than get their work finished they could ‘lap water’ from a nearby horse pond. His new house was dubbed locally as ‘Lapwater Hall’ and carries that moniker to this day. And what about Mr Craddock? Well, in some sort of karmic fate he was discovered to be the infamous highwayman Cutter Lynch who gave his earless horse, Brown Meg, prosthetic wax ears when holding up stage coaches to disguise his very unique and recognisable horse. He was shot by the Bow Street Runners near the house and died of blood loss and possible drowning in shallow water thick with reeds. [Source: ‘Legends of Leigh’ by Sheila Pitt-Stanley 1989, who gives a much more thrilling account]

In the podcast Brian mentions a few times the character Goldspring Thompson in relation to the Nore Mutiny of 1797. Goldspring had supposedly escaped the mutiny when events looked like turning against the mutineers and I suppose he saw what retributions might be meted out to him and others if he stayed on board. His story of jumping overboard and hiding out in the reeds probably survives because he lived such a long life, dying in 1875, and no doubt he told his tale many times in the local pubs of the old town.

Thinking about the richness of these old stories about mutineers and highwayman around the old town of Leigh-on-Sea seem understandable to me when you think that nearly all of these tales derive from the late eighteenth century or nineteenth century; old enough to be mythic but young enough to be part of an oral tradition passed down through 4 or 5 generations. Southend did not really exist in any extensive sense at this time, only growing in the later nineteenth century as the train line expanded eastwards from London and Leigh was the hub for boats from across the world. I think this explains the reason there are less tales of high adventure from Southend itself.

The John Constable tale that forms mine and Brian’s quest in the podcast was one I had known for some time but there had been little attention on it. Constable had painted the nearby Hadleigh Castle, first in 1814 when he sketched it and then the actual painting in 1829. The Sketch resides in the Tate Gallery, London while you would have to visit the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Conneticut to see the finished painting. I had read in several references that John had stayed with his uncle Thomas in Leigh-on-Sea when he came to make the sketches.

John Constable’s ‘Hadleigh Castle’ (1829)

This didn’t seem far fetched at all so the hope was that finding some remains of the original Juniper’s Cottage would give us some spiritual closeness to it all. The day we chose to visit was in early December and without my gloves it became painful holding the recorder to capture our journey. You may be able to hear me gasping a bit as we walk and talk, it was that cold. I should have taken my warmer jacket.

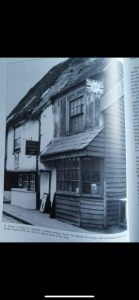

Juniper’s Cottage doesn’t exist any more and Brian later discovered through his research that it was mostly demolished in 1952 but you can see the rough shape of the building still. I tried to get a photo of the building that day and then subsequent days but it was always so busy and in winter lockdown it felt a place to steer away from. I managed to get the shot on the left in a very cold and bitter early January evening while to the right you can see how it looked, most likely in the 1930s or 40s. It was named after Joe Juniper who turned it into a fishmongers and tearoom some time in the nineteenth century.

People in Leigh are very proud of these stories and there’s lots more of them. The pirate’s grave at St. Clement’s Church, the near death of Henry IV as he crossed the Thames to Leigh from the Isle of Sheppey during a storm and the oyster wars with the men of Kent in the early eighteenth century. These are not stories that define national identity or inform this island’s greater heritage, it’s parochial and light but what it does show is that there is a desire to keep these small events in the lives of those who lived here a couple of hundred years ago alive today and to keep a thread to an older, perhaps less cluttered, era in an area that is continually being developed and added to as the need for housing to accommodate the growing overspill of communities from London grows. The Government’s ‘Estuary 2050’ scheme plans to significantly develop this part of the Thames shore (and others) for housing and economic growth.

This desire for a personal and local history that can be publicly owned and recounted by the community was very evident in the Joscelyne’s Beach story which I discussed with poets Jo Overfield and Ray Morgan. I worked in an independent bookshop in 2000 and remember Arthur Joscelyne’s daughter coming into the shop with the book. We sold lots and people would come in for years afterwards wanting copies. Those who bought it knew Arthur or his family and always wanted to impart to me their own experiences and memories of the beach and the area.

I collected a lot of stories that way, listening to people in the bookshop and some made their way into my songs. For example, there was one elderly couple who came in with their son, Michael (who must have been in his fifties and suffered various health issues). They would recount stories about using the Medway Queen, a pleasure boat over in Kent and heading over to Margate from Southend Pier. Michael’s father was drowned in World War II. I thought this incredibly sad and I recall they said something about the Captain in charge being a man called Boutwood. Having just looked it up I wonder whether his father died on the HMS Fantome which was mined in 1942 off Bizerte. It was this story that inspired my song ‘Night Water’ from the album, ‘The Water or the Wave’.

Sadly booksellers in Leigh-on-Sea have dwindled in recent years, although Leigh Gallery Books is a must for your secondhand needs. The personal and hidden histories remain however and there’s still more to uncover. With Clifftown I suppose I have laid my own little history down by these silver waters, maybe to be retold by the next person along.